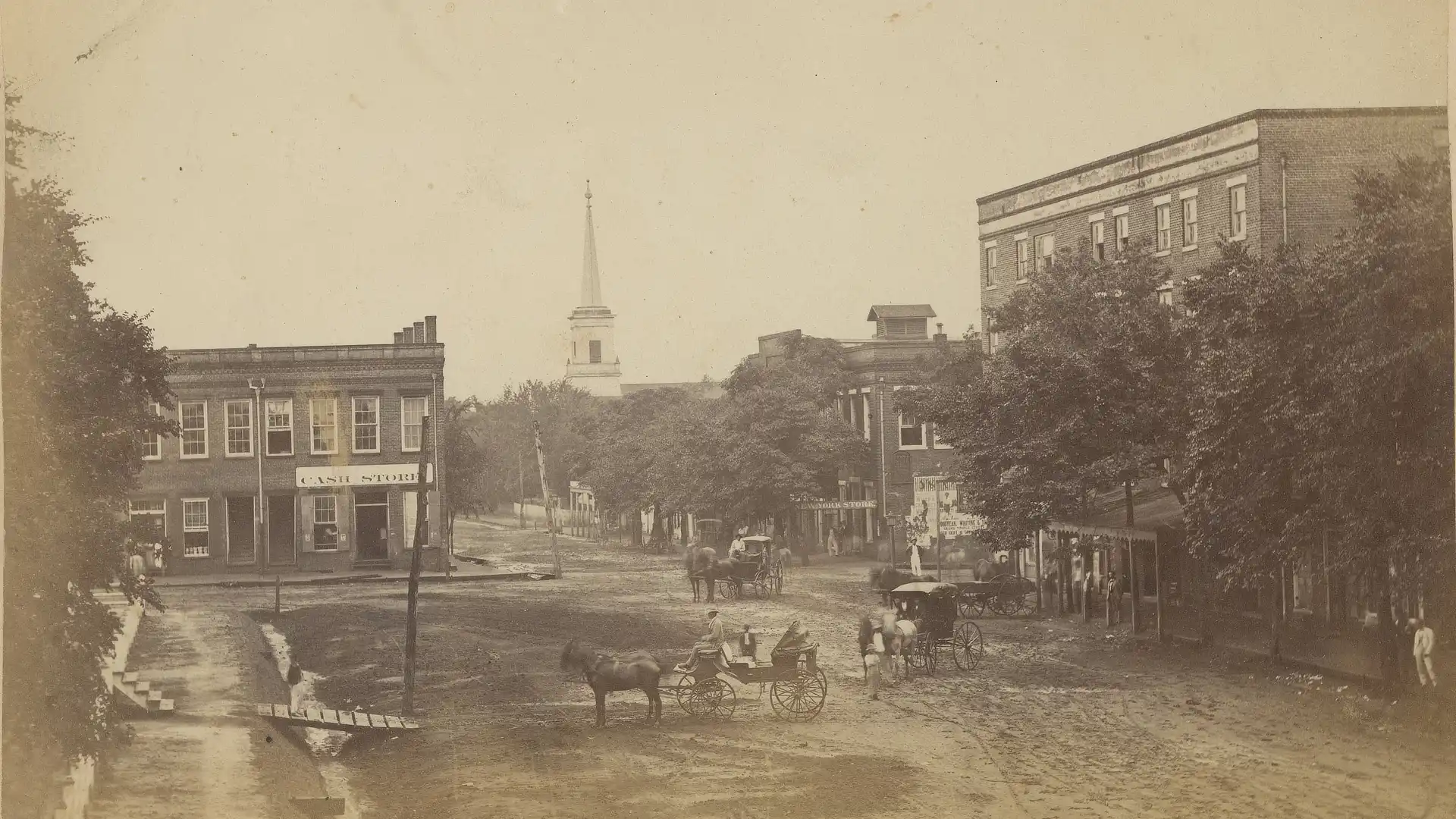

In 1841, the founding of Howard College in Marion, Alabama, was not a random occurrence. In the rough-and-tumble frontier town filled with whiskey taverns and rowdy boys, a fledgling Christian liberal arts college seemed out of place. But the Holy Spirit was at work. Inspired by the life of its namesake, 18th-century British reformer John Howard, the founders envisioned a college with the purpose of transforming local wild-eyed boys into useful and enlightened Christian citizens.

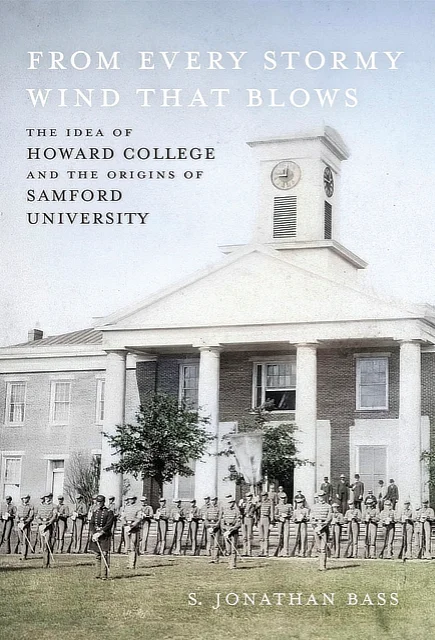

In his latest book, From Every Stormy Wind That Blows: The Idea of Howard College and the Origins of Samford University, Jonathan Bass provides a thorough and comprehensive history, spanning from the early 1800s to the early 20th century. Bass, who serves as university historian and professor in Howard College of Arts and Sciences, was asked to write this scholarly account by President Emeritus Andrew Westmoreland. His research spanned several years, reaching its culmination when Louisiana State University Press published the book earlier this year.

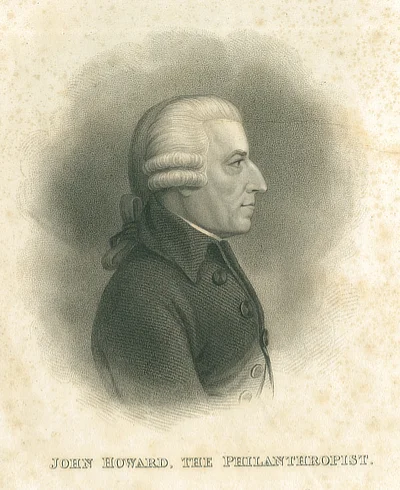

Bass emphasizes the founders’ notable choice for the college’s name. Instead of naming the institution after a founder, like James DeVotie, or a prominent supporter, like Julia Barron, Howard College was named after a man who had no direct connections to the Alabama frontier. In fact, Howard had died more than 50 years earlier in 1790. “DeVotie suggested naming the new institution after the type of person he and other founders hoped these young men (and later women) would become,” Bass explains. “Throughout the early 19th century, John Howard was still remembered worldwide. His virtues were the four founding principles of what would become Howard College.”

Bass emphasizes the founders’ notable choice for the college’s name. Instead of naming the institution after a founder, like James DeVotie, or a prominent supporter, like Julia Barron, Howard College was named after a man who had no direct connections to the Alabama frontier. In fact, Howard had died more than 50 years earlier in 1790. “DeVotie suggested naming the new institution after the type of person he and other founders hoped these young men (and later women) would become,” Bass explains. “Throughout the early 19th century, John Howard was still remembered worldwide. His virtues were the four founding principles of what would become Howard College.”

As the book explains, “DeVotie and other Marion Baptists imagined that their new Christian college would become a community of learners who accepted and furthered the Gospel message (faith), pursued a deeper understanding of God’s universe (intellect), served their community and country (benevolence) and exemplified good moral character (virtue). Putting these four principles into action required a unifying curricular model that demonstrated Howard College’s mission and identity.”

As the book explains, “DeVotie and other Marion Baptists imagined that their new Christian college would become a community of learners who accepted and furthered the Gospel message (faith), pursued a deeper understanding of God’s universe (intellect), served their community and country (benevolence) and exemplified good moral character (virtue). Putting these four principles into action required a unifying curricular model that demonstrated Howard College’s mission and identity.”

The idea of Howard College was rooted in “its founders’ firm commitment to orthodox Protestantism, the tenets of Scottish philosophy, the British Enlightenment’s emphasis on virtue, and the moral reforms of the age. From the Old South, through the Civil War and Reconstruction, to the New South, Howard College adapted to new conditions while continuing to teach the necessary ingredients to transform young southern men.”

Samuel Sterling Sherman, who would become the college’s first president, was appointed to spearhead the development of Howard College’s first liberal arts curriculum. He established a “common core of knowledge” where the classic texts were complemented by the Scriptures. For, as Sherman believed, “an education at a Christian college was incomplete and illiberal without the Bible serving as the sine qua non [the essential element] of classical texts.”

Samuel Sterling Sherman, who would become the college’s first president, was appointed to spearhead the development of Howard College’s first liberal arts curriculum. He established a “common core of knowledge” where the classic texts were complemented by the Scriptures. For, as Sherman believed, “an education at a Christian college was incomplete and illiberal without the Bible serving as the sine qua non [the essential element] of classical texts.”

Throughout the 19th century, Howard College “faced challenges both within and without. As with other institutions in the South, slavery played a central role in its founding, with most of the college’s principal benefactors, organizers and board of trustees earning financial gains from enslaved labor. The Civil War swept away the college’s large endowment and growing student enrollment, and the school never regained a solid financial footing during the subsequent decades.”

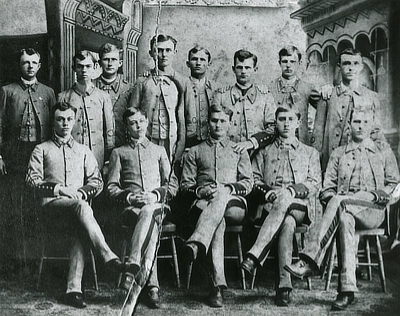

In 1871, under the leadership of James T. Murfee, the college adopted the model of a classic military school. Murfee revitalized the college’s academic program, creating a new academic structure based on small class size and individual attention and practice. He also imposed military discipline. Students were required to wear military uniforms on public occasions, and the college began to resemble a military academy. By the end of that decade, military drills were a daily routine for many students.

In 1871, under the leadership of James T. Murfee, the college adopted the model of a classic military school. Murfee revitalized the college’s academic program, creating a new academic structure based on small class size and individual attention and practice. He also imposed military discipline. Students were required to wear military uniforms on public occasions, and the college began to resemble a military academy. By the end of that decade, military drills were a daily routine for many students.

Throughout these years, Howard College teetered on the edge of financial ruin. In 1884, facing bankruptcy, the college’s property was put up for public auction on the steps of the Perry County Courthouse. The property was saved when two members of the Board of Trustees submitted the only bid. They, in turn, sold the property for $1 to the Alabama Baptist State Convention, which allowed Howard College to continue to operate.

In 1887, the Alabama Baptist State Convention decided to move Howard College from its birthplace to a new campus in East Lake, on the outskirts of Birmingham. The move was a point of contention with opposition on both sides. Many believed that Birmingham was the “optimal educational center” of the state. Yet for others, Birmingham was a detestable city, calling it an “immoral place for a college founded on the principles of virtue and faith.” But the convention was decisive; the 1887-88 academic year was the first at the new East Lake campus.

President Benjamin Franklin Riley, a well-known New South economic booster, fought to restore the college’s financial health. Despite his best efforts, Howard College continued to struggle economically, but his recruitment efforts, which led him to travel throughout the state, proved fruitful. In 1890, Howard College enrolled its largest class to date, comprised of 206 students. Finally, with the financial assistance from several local bankers, the college gained some footing, enabling Howard College to enter the 20th century with a measure of financial stability.

As the book explains, “Although problems remained, the end of the century provided a major turning point in the history of Howard College. The stormy winds of debt that had enveloped the college for six decades finally eased—leading to a sustained period of unprecedented growth and expansion.”

With the publication of this book, the Samford University community is invited to explore the highs and lows, the successes and failures, of an institution that has weathered the “stormy burdens of southern history: from the rowdy Frontier South of drinking, fighting, and mayhem to the Old South of cotton, plantations and slavery to the New South of iron, steel and segregation.”

In the book’s introduction, Bass clearly states its purpose: “to reconstruct the ‘idea’ of Howard College and to recover the institution’s history and original mission—all within the context of southern history.” From Every Stormy Wind that Blows does just that.

From Every Stormy Wind that Blows can be purchased online at LSU Press (use the code LSUSAVE40 at checkout for a 40% discount) or on campus at the Samford Shop.

This story was first published in the summer 2024 issue of Seasons magazine. See more from this issue at samford.edu/news/seasons.