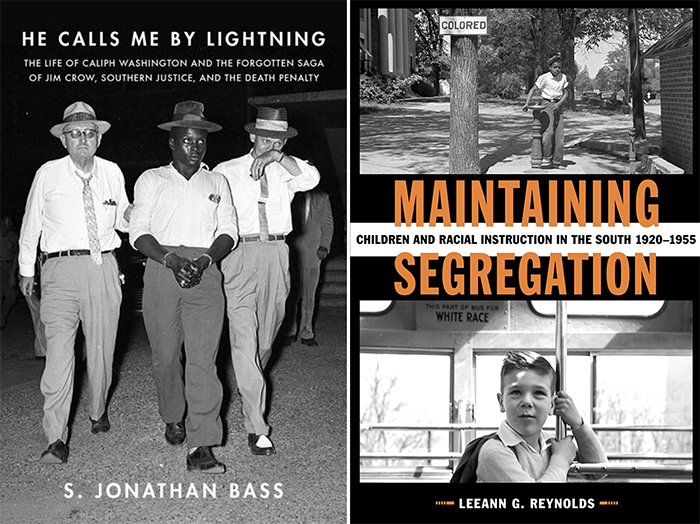

This spring Samford history professors S. Jonathan Bass and LeeAnn G. Reynolds published new books exploring the history and legacy of racial injustice in the American south.

Bass’s He Calls Me By Lightning: The Life of Caliph Washington and the Forgotten Saga of Jim Crow, Southern Justice, and the Death Penalty follows his Pulitzer-nominated Blessed Are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King, Jr., Eight White Religious Leaders, and the "Letter from Birmingham Jail" (2001).

In the new book, Bass explores the long ordeal of Caliph Washington, a black man unjustly convicted of the 1957 murder of police officer James “Cowboy” Clark amidst the reflexive racism of Civil Rights Era Alabama. Washington endured more than a decade of prison, multiple trials, overturned convictions and repeated rescue from the electric chair. Over the course of his ordeal, Washington experienced a spiritual transformation from an angry young man to a humble Christian evangelist who shared his Job-like faith both inside and outside prison.

“The broad historical significance of Caliph Washington’s life and trials serve as an avenue to explore the measures used by white southern officials (lawmen, lawyers, judges and juries) to enforce Jim Crow ‘justice’ at the local level, especially through race-based jury exclusion,” Bass wrote. “He Calls Me by Lightning forces twenty-first century readers to reexamine systematic racism of the Jim Crow era and consider how the criminal justice system continues to discard the lives of young black men today.”

Reynolds’s Maintaining Segregation: Children and Racial Instruction in the South, 1920-1955 explores how black and white children in the early twentieth-century South learned about segregation in their homes, schools, and churches.

As the system of segregation evolved throughout the early twentieth century, generations of southerners came of age having little or no knowledge of life without institutionalized segregation. In her new book, Reynolds examines the motives and approaches of white and black parents to racial instruction in the home and how their methods reinforced the status quo. Whereas white families sought to preserve the legal system of segregation and their place within it, black families faced the more complicated task of ensuring the safety of their children in a racist society without sacrificing their sense of self-worth. Schools and churches functioned as secondary sites for racial conditioning, and Reynolds traces the ways in which these institutions alternately challenged and encouraged the marginalization of black Americans both within society and the historical narrative.

In order for subsequent generations to imagine and embrace the sort of racial equality championed by the civil rights movement, they had to overcome preconceived notions of race instilled since childhood. Ultimately, Reynolds’s work reveals that the social change that occurred due to the civil rights movement can only be fully understood within the context of the segregation imposed upon children by southern institutions throughout much of the early twentieth century.